When my boyfriend said ‘Let’s go to Chernobyl’, I heard ‘Let’s explore abandoned spaces’. Saying yes was a reflex and gawking at disaster porn a compulsion. But planning a trip is never so simple. When I agreed, I entered into a labyrinth of safety concerns and ethical debates that required me to reflect on the role of responsible tourism in a capitalist economy.

Although most Westerners know Chernobyl as the 1986 nuclear catastrophe, the event is foggy in our cultural memory. A brief lesson: Chernobyl is the name of the town where the eponymous nuclear power plant is located. In the 1960s, the Soviet Union built the plant and its six reactors to provide energy for Kiev, Ukraine’s capital. The nearby town of Pripyat was founded in February 1970 to accommodate the workers and their families. The explosion rendered these areas uninhabitable.

Unlike American nuclear stations which fortified reactors with containment units, the Soviets didn’t build protective barriers. Their presence may have mitigated the fall out but it couldn’t have prevented the accident. On April 26th, 1986 reactor number 4 failed, caught fire and began spewing radioactive smoke. This dust blew north through Belarus and caused the country to lose 20% of its land (Ukraine, in comparison, lost 8%). The dust reached Sweden by morning and raised radiation levels throughout Europe.

What happened in the days and years following the disaster remains hazy. Even today, most Ukrainians aren’t aware that the site can be visited despite the fact that it drives foreign tourism.

Touring isn’t as easy as driving your car up to the reactor. The plant still functions and is ringed by two restricted access zones: one at 30 kilometres from the reactor and one at 10 kilometres. Anyone over eighteen can enter for the price of a pre-booked group tour, roughly $100. Overachievers can purchase excursions up to four days long or hire a private guide. Regardless of how you enter, you’ll submit your passport to authorities at checkpoints and adhere to radiation scans before leaving. Flying to Ukraine to begin with is even harder.

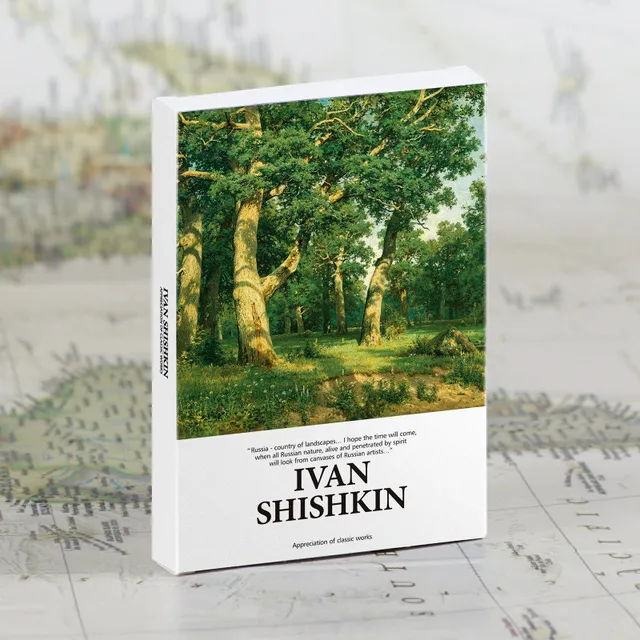

I might be biased because on my flight I broke my heart reading Chernobyl Prayer, Nobel prize winner Svetlana Alexievich’s oral history of the event. Collecting accounts from survivors, Alexievich presents first-person stories about abandoning home and the stigma associated with being from Chernobyl. I shoved the book in front of my boyfriend’s sleeping face. This is what we’re going to see! Then came the epilogue. In crisp prose, Alexievich damns those who visit Chernobyl as an exciting excursion. She damns us voyeurists of suffering. We do not understand.

While dismissing safety concerns was easy — airport scans have probably exposed me to more radiation than remains in the entire Chernobyl exclusion zone — the suggestion that dropping in was irresponsible nagged at my conscience. What was the difference between tromping around an environmental disaster and touring Auschwitz or gawking at Ground Zero? My mind searched for answers. Answers I could only find in Chernobyl.

I began to form a response at the pick-up location in Kiev. Our tour organizer wore a black t-shirt with Hard Rock Café Chernobyl emblazoned on it. The van featured a split-face photo of a blonde girl: in Kiev she wore a gas mask, in Chernobyl she smiled. Although I anticipated finding an emotional connection, so far I had only found the tourism industry.

Not much separates the 30 kilometer exclusion zone from what lies beyond its border besides a passport checkpoint. Some elderly residents have returned and workers building the shell to seal off the damaged reactor live in dormitories. There’s a hotel for visitors on longer tours. While there might not be much life here, neither is there much horror.

The same can be said for Pripyat and the reactor, both of which are in the 10 kilometer exclusion zone. Nature reclaimed Chernobyl during the intervening thirty-years. Plush trees line the roads, fat catfish swim in the Pripyat River and sun gilds the crumbling walls. Even when I should have gasped at dust-encrusted gas masks or decaying floorboards, I felt joy. Although the explosion speaks to humanity’s self-destructive power, nature’s triumph suggests that humans still don’t understand how to live in harmony with their environment. I didn’t find anything daring in Chernobyl. Instead, I found calm.

Perhaps this calm reflects the immorality Alexievich railed against. Perhaps this joy proves my inability to understand the disaster’s magnitude. Or perhaps it reveals that we’re still anxious about remembering Chernobyl because doing so means accepting our capacity for self-destruction and ignorance toward nature. We may know how to manipulate atoms, but Mother Nature knows how to manipulate us.

And she doesn’t always welcome us. While tourism to Chernobyl questions regarding personal safety and the right to access, the area cannot be hermetically sealed. Nor should it be. Preventing visitors will cause the event to fade from our memory, while implying that the vast region is dead. As Alexievich and the catfish swimming in the Pripyat river demonstrate, the area bursts with life. But it’s an uncomfortable life. It’s the life of utopian dreams and human exile. Visiting Chernobyl is not right or wrong. It is an exercise in critical reflection. And that’s where our ethics fail.

This is a guest post by Emilia Morano-Williams.

Emilia Morano-Williams is a freelance food and travel writer based in New York. She has lived in Bristol, UK, Pavia, Italy and London. When not traveling and writing about it, she enjoys arguing about Italian food culture, expanding her magazine collection and attempting to learn Swedish.

Emilia Morano-Williams is a freelance food and travel writer based in New York. She has lived in Bristol, UK, Pavia, Italy and London. When not traveling and writing about it, she enjoys arguing about Italian food culture, expanding her magazine collection and attempting to learn Swedish.